So here is one outstanding problem ...

In cognitive science ... little to say about actions whose purposes

involve things the motor system doesn’t care about---your motor system

doesn’t care whether the plane you are stepping is headed for Milan or

for Rome, but this sort of difference can affect whether your actions succeed or fail.

You might just say that the two disciplines are talking past each other,

or you might say that they are offering two complementary but independent

models of action.

Call this the ‘Two Stories View’ (or divorced, but living together).

[Alt: quick version --- Ask a phil about action and they'll tell you a story about

intentions and processes of practical reasoning. Ask a psych ...

Do we need to connect these largely separate stories or is it

fine for each discipline to tell its own story about action? Let's see ...]

I think there’s a problem.

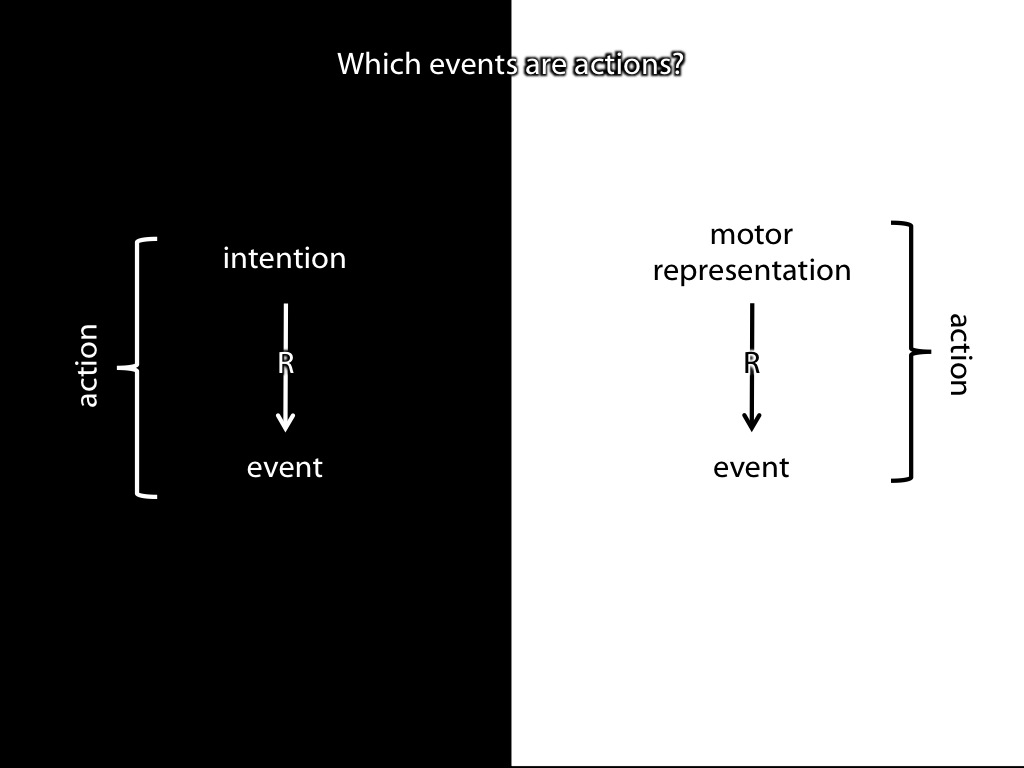

If you ask scientists about action, they will tell you a story about motor representations

and processes.

And if you ask philosophers, they will tell you a story about intentions and practical reasoning.

Both stories seem reasonably compelling, and there is even evidence for one of them.

How are the two stories related?

One possibility is that they are two ways of talking about a single thing.

But this doesn't seem right because the stories explain different, if overlapping, phenomena.

The philosophers are interested in everything from extremely large scale actions which may take

days, like the action of competing in the Tour de France to very small scale actions such as the

action of turning a crank.

The psychologists, by contrast, are mostly interested in the small and very small scale actions.

So there is some overlap in actions like turning a crank, breaking an egg, taking and eating a

biscuit.

How are the two stories related if they are not using different words for the same thing?

Another possibility is that they are just completely unconnected. One is about the ‘space of reasons’,

another about the space of something else.

But this possibility is hard to square with the idea that intentions are causal elements in

processes which, often enough, result in the body moving.

It seems that the practical reasoning has to influence the motor processes, and perhaps conversely

too.

As Elisabeth suggested in a ground-breaking ‘dynamic theory of intentions’

(Pacherie, 2008, p. 181ff.), it is plausible that motor representations can

inherit goals from, and be influenced by, intentions (pp.~186--7).

Just here we face a practical problem. Because of the separation of concerns,

there very little research on how the two stories---the one about intentions and practical reasoning,

and the one about motor representations and processes---might join up.

So it is that the interface problem falls into the gap between philosophers’ concerns with practical

reasoning and scientists’ concerns with motor control.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

compatible stories about different things?

contradictory stories about one thing?

aspects of a single larger story?

habitual processes, motivation, affect, reasons, knowledge, experience, autonomy, control, attention, agency ...?

We did just scratch the surface.