Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Pacherie’s Objection to Bratman on Shared Intention

‘I am skeptical that all intentional joint actions require the sophistication in ascribing propositional attitudes that Bratman’s account appears to demand.

To motivate this skepticism, I’ll turn to [...] empirical evidence that young children engage in what appears to be intentional joint action despite lacking this conceptual sophistication.’

(Pacherie, 2013, p. 2)

1. Bratman’s account requires sophistication in ascribing propositional attitudes coordinating planning. ✓

2. There is an age at which children engage in joint action ✓

3. while lacking this sophistication. ✓

∴ Not all joint action involves the shared intentions Bratman characterises.

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

1. Bratman’s account requires sophistication in ascribing propositional attitudes coordinating planning. ✓

2. There is an age at which children engage in joint action ✓

3. while lacking this sophistication. ✓

∴ Not all joint action involves the shared intentions Bratman characterises.

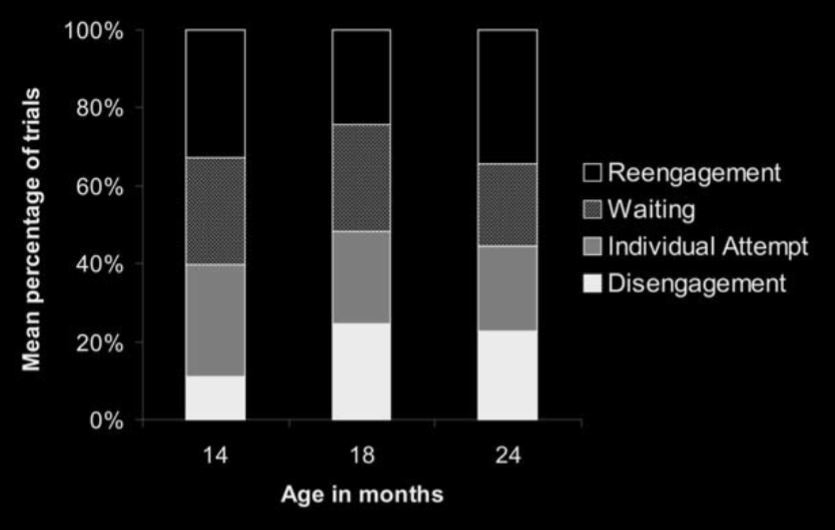

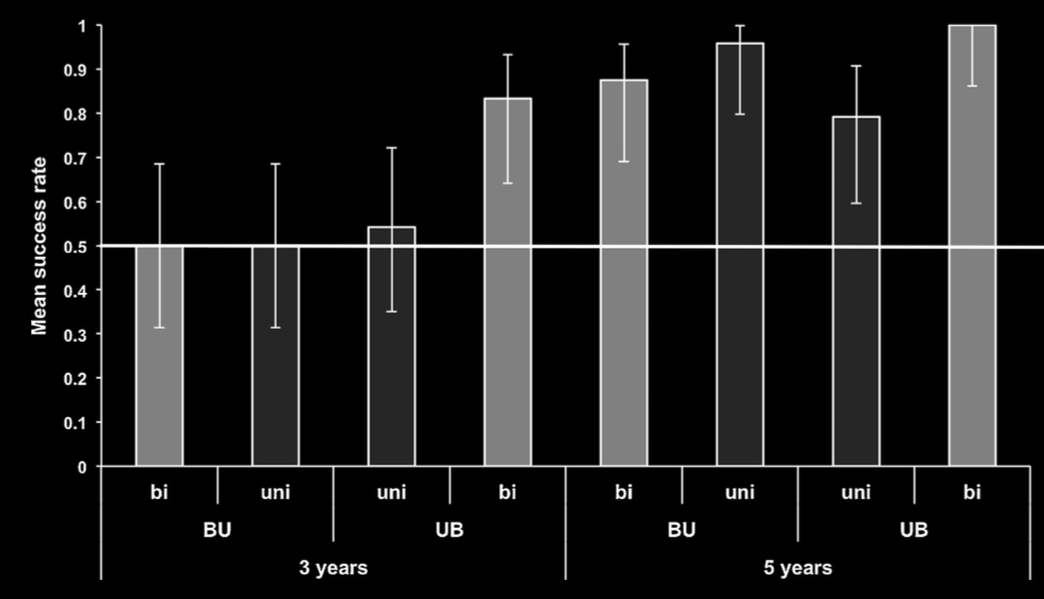

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

Warneken & Tomasello (2007, p. figure 4)

Infants’ ‘attempts to reactivate the partner in interruption periods indicate that they were aware of the interdependency of actions—that the execution of their own actions was conditional on that of the partner’

Warneken & Tomasello (2007, pp. 290--1)

1. Bratman’s account requires sophistication in ascribing propositional attitudes coordinating planning. ✓

2. There is an age at which children engage in joint action ✓

3. while lacking this sophistication. ✓

∴ Not all joint action involves the shared intentions Bratman characterises.

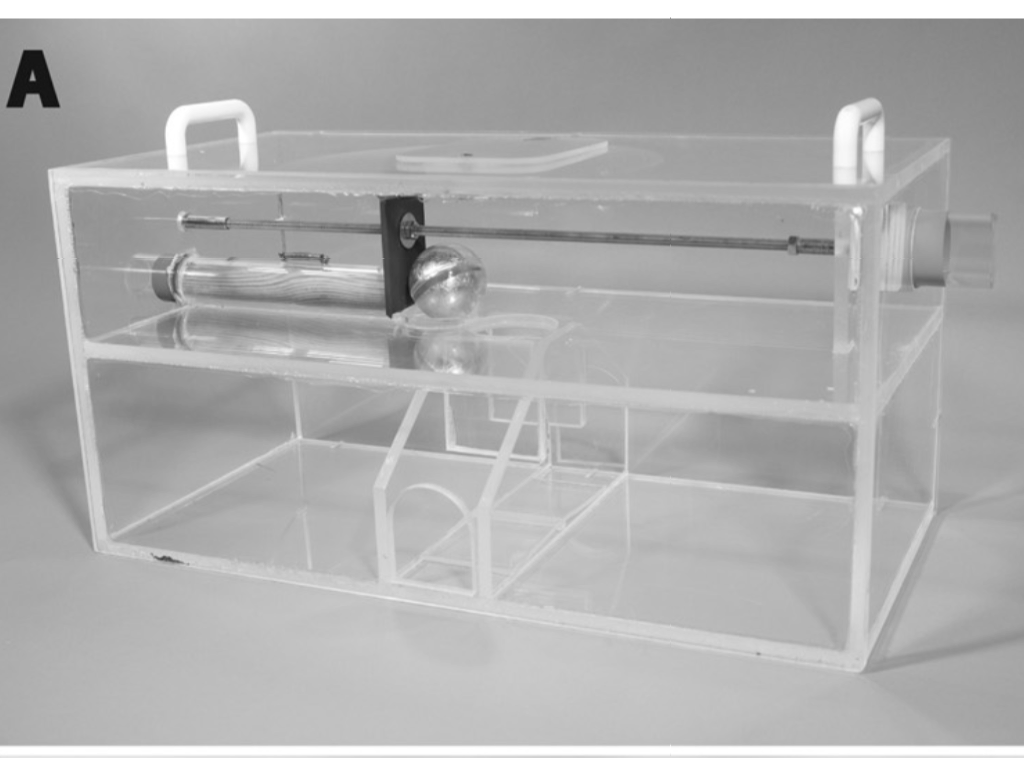

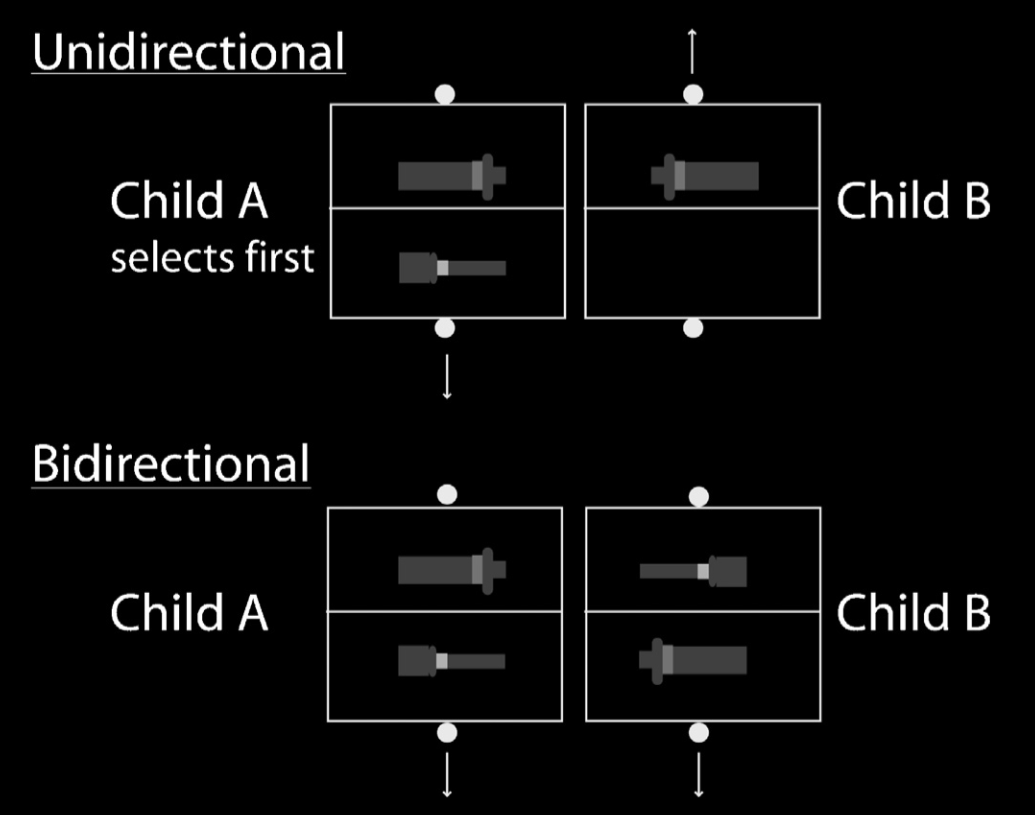

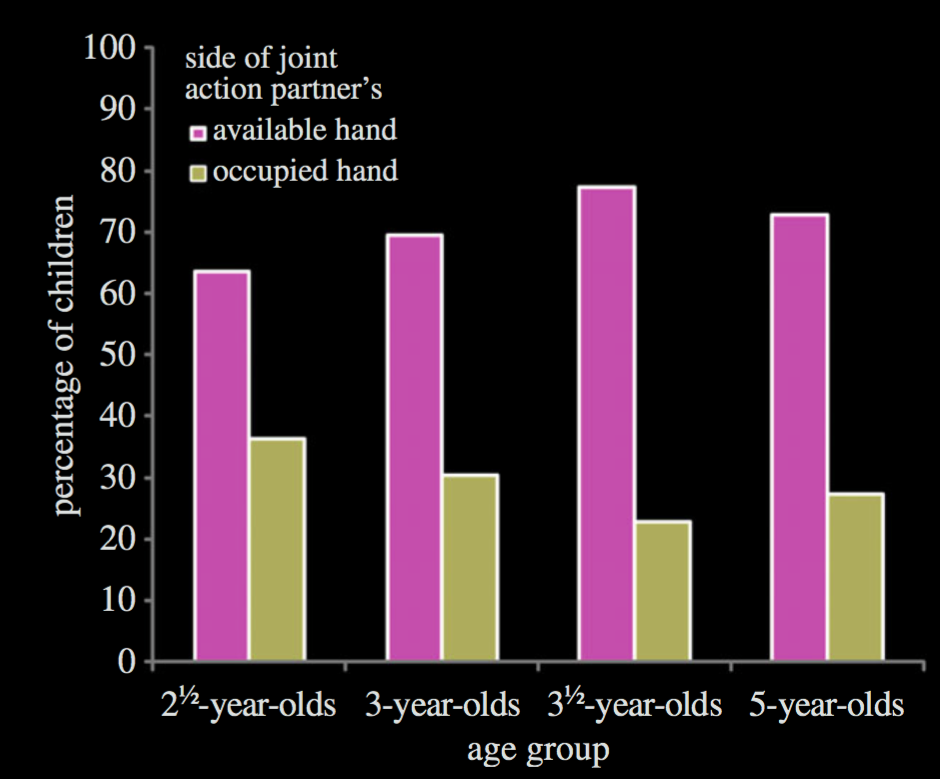

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 1

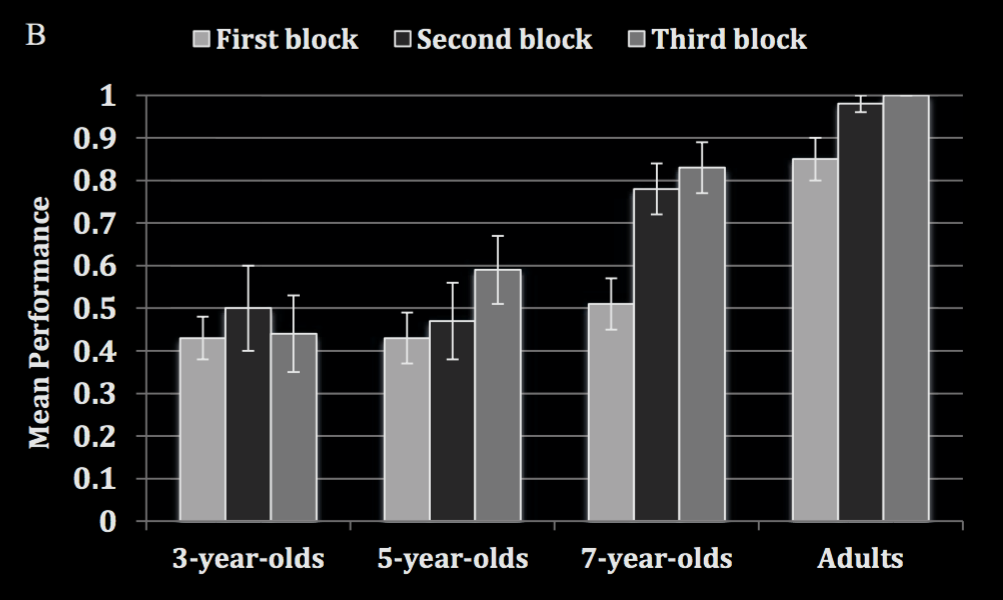

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 2B

‘3- and 5-year-old children do not consider another person’s actions in their own action planning (while showing action planning when acting alone on the apparatus).

Seven-year-old children and adults however, demonstrated evidence for joint action planning. ... While adult participants demonstrated the presence of joint action planning from the very first trials onward, this was not the case for the 7-year-old children who improved their performance across trials.’

Paulus et al, 2016 p. 1059

1. Bratman’s account requires sophistication in ascribing propositional attitudes coordinating planning. ✓

2. There is an age at which children engage in joint action ✓

3. while lacking this sophistication. ✓

∴ Not all joint action involves the shared intentions Bratman characterises.

appendix

more evidence against the prediction

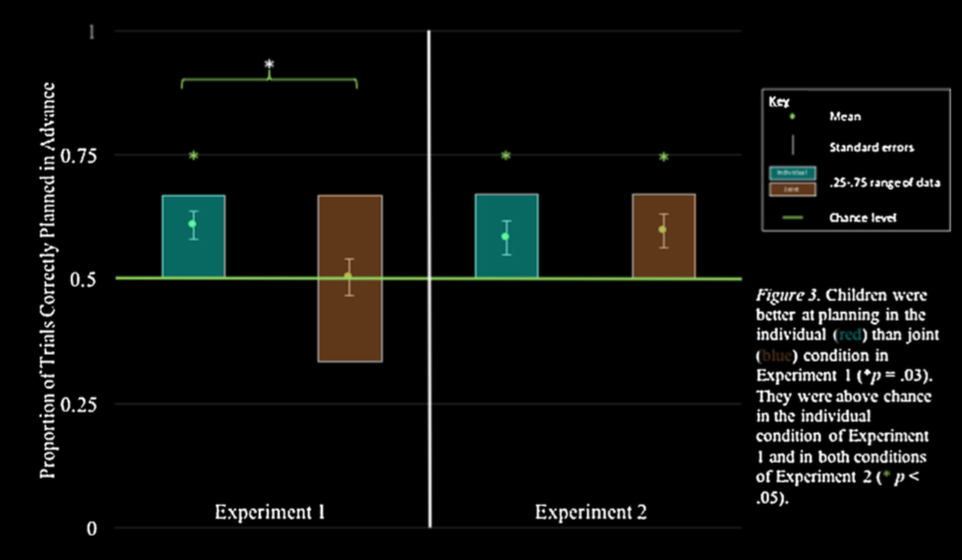

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 1A

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 2

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 3

‘shared intentional agency [i.e. ‘joint action’] consists, at bottom, in interconnected planning’

Bratman, 2011 p. 11

Hypothesis (Carpenter): One- and two-year-olds have shared intentions as characterised by Bratman.

Prediction: They should be capable, at least in some minimally demanding situations, of coordinating their plans with another’s.

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Mismatch:

Bratman’s account of joint action

vs

1- to 3-year-olds’ joint action abilities

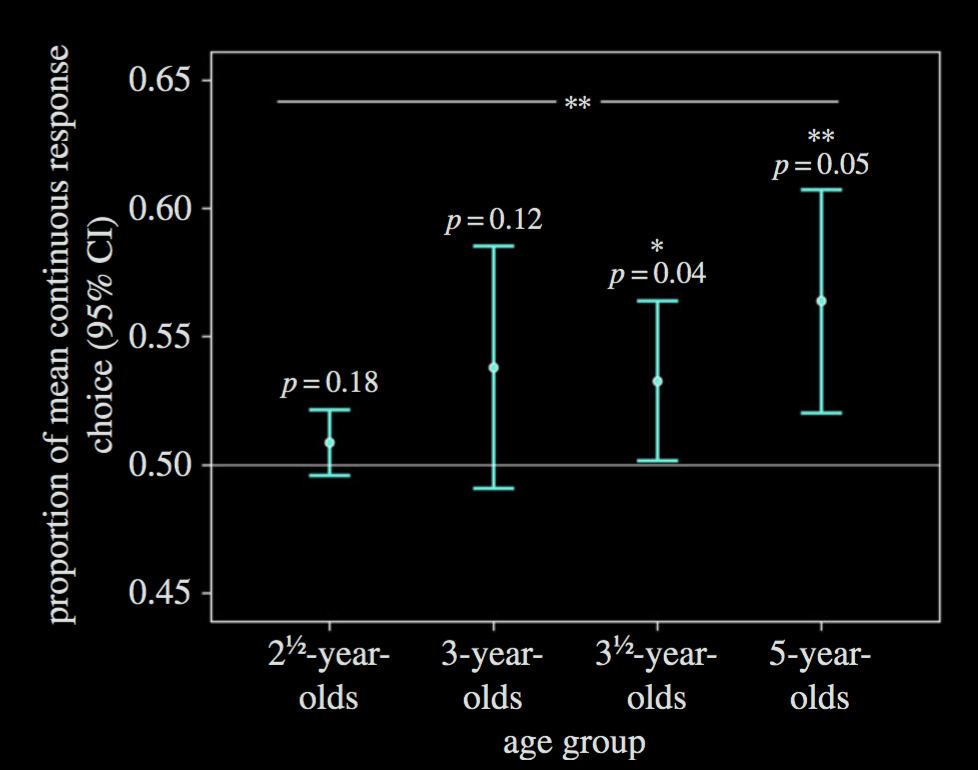

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1A

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1B

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1C

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 2

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 3

‘shared intentional agency [i.e. ‘joint action’] consists, at bottom, in interconnected planning’

Bratman, 2011 p. 11

Hypothesis (Carpenter): One- and two-year-olds have shared intentions as characterised by Bratman.

Prediction: They should be capable, at least in some minimally demanding situations, of coordinating their plans with another’s.

Gerson et al, 2016 figure 1B

Gerson et al, 2016 figure 3