Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Minor Puzzle about Habitual Action

Which of these are when are these habitual actions:

doing your teeth;

smoking tobacco;

watching TV;

cycling the same route to work every day?

habitual vs habitual

‘A habitual action, state, or way of behaving is one that someone usually does or has, especially one that is considered to be typical or characteristic of them.’

--- collinsdictionary.com

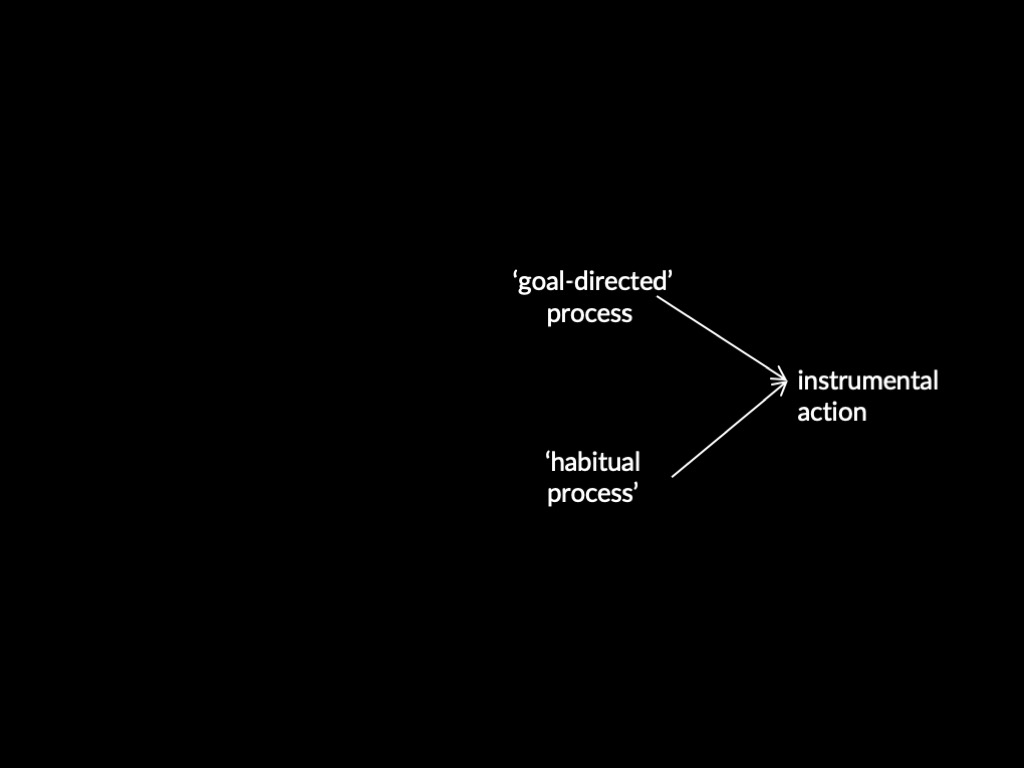

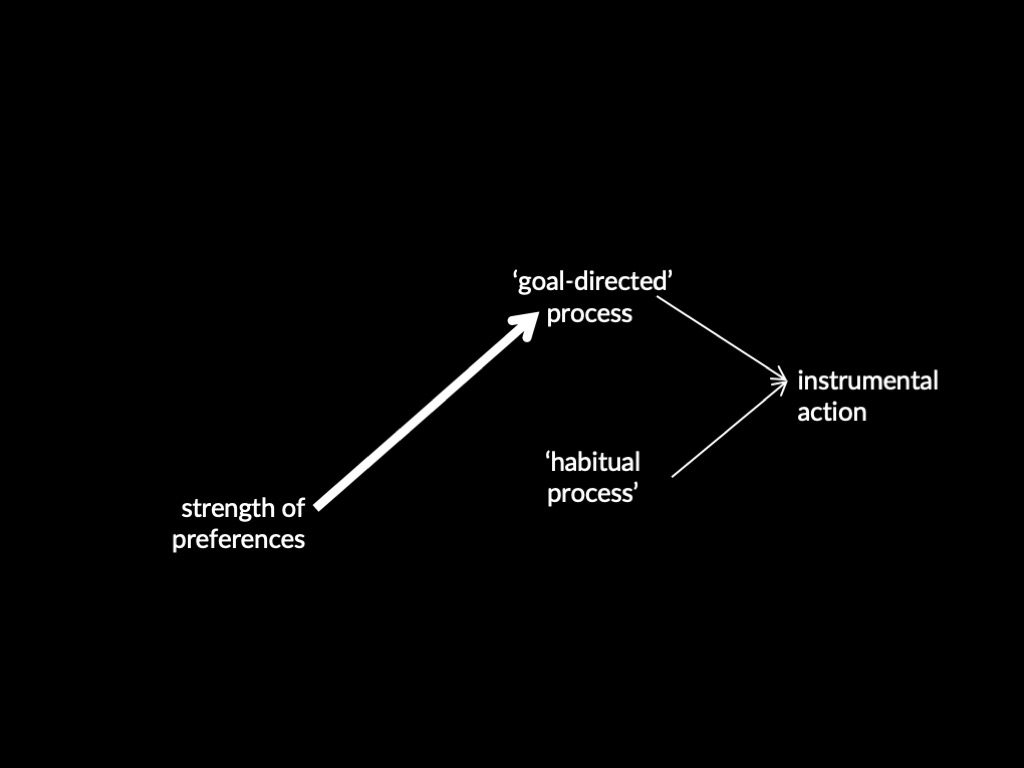

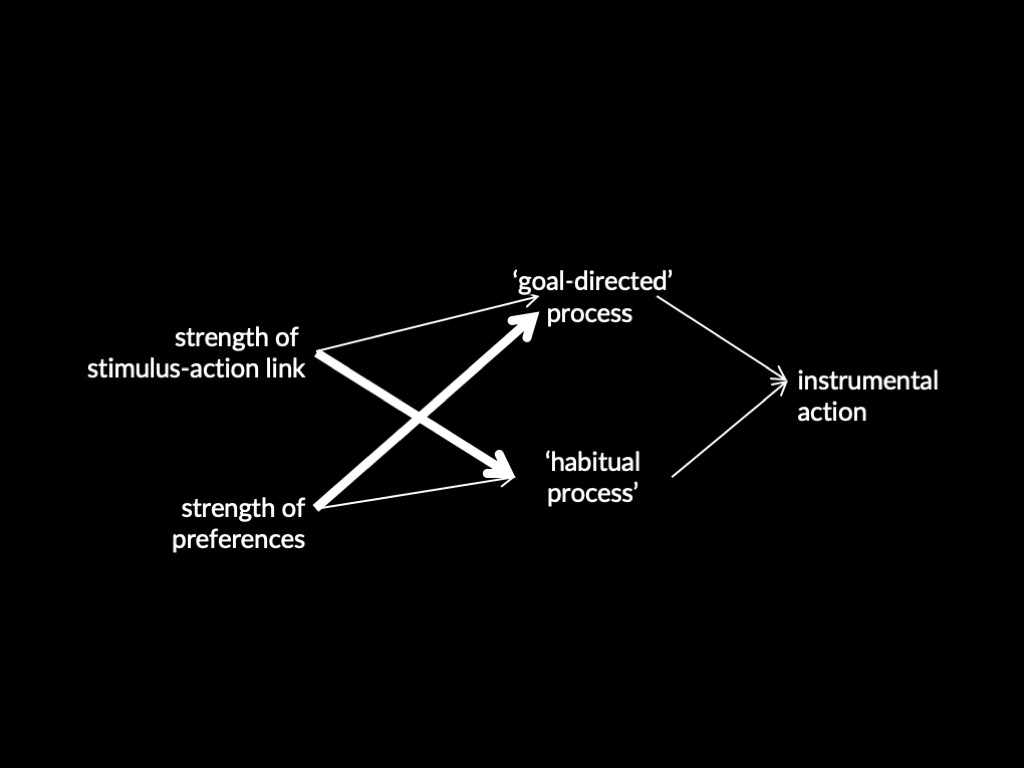

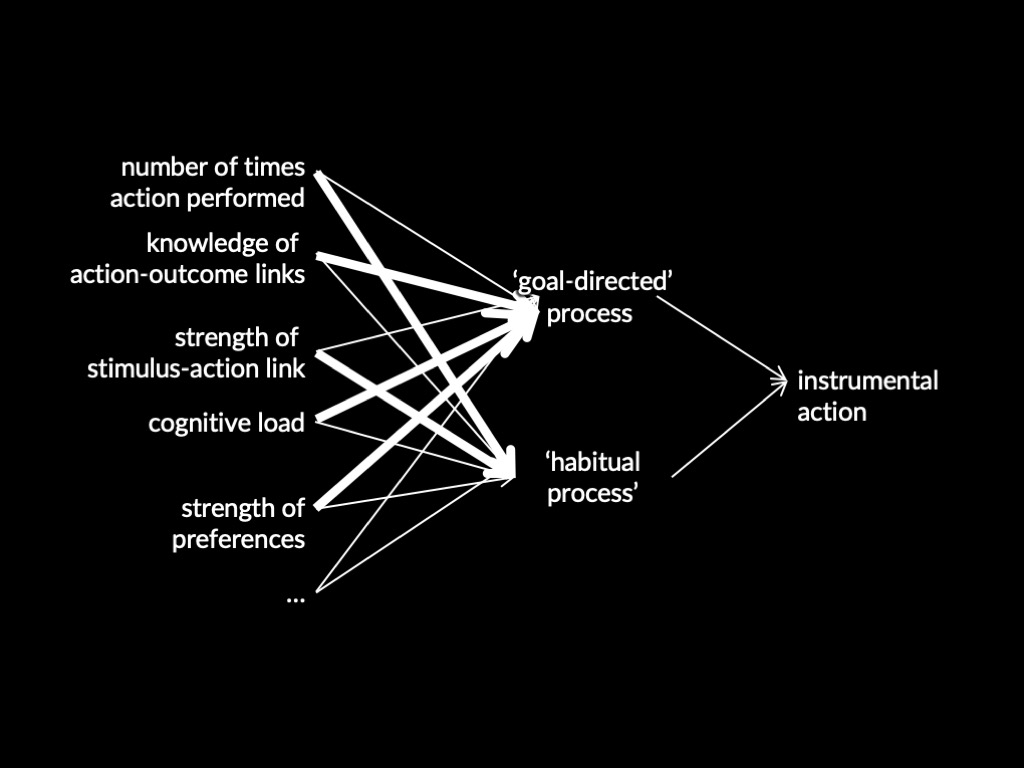

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished] p(class=theCls)Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

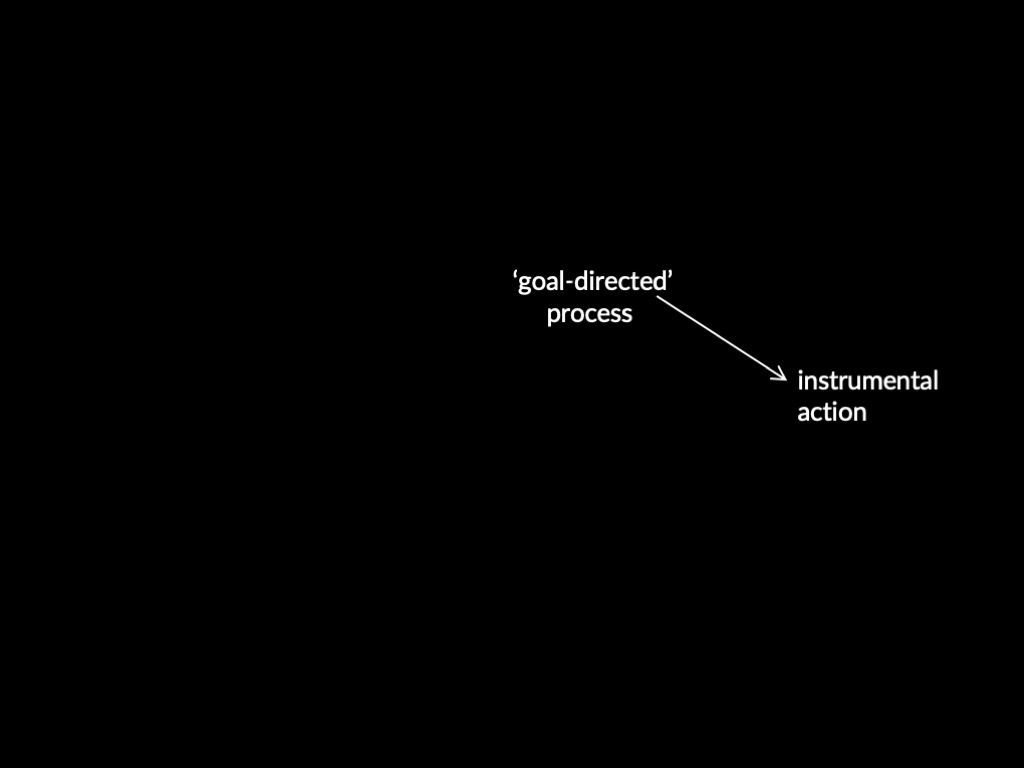

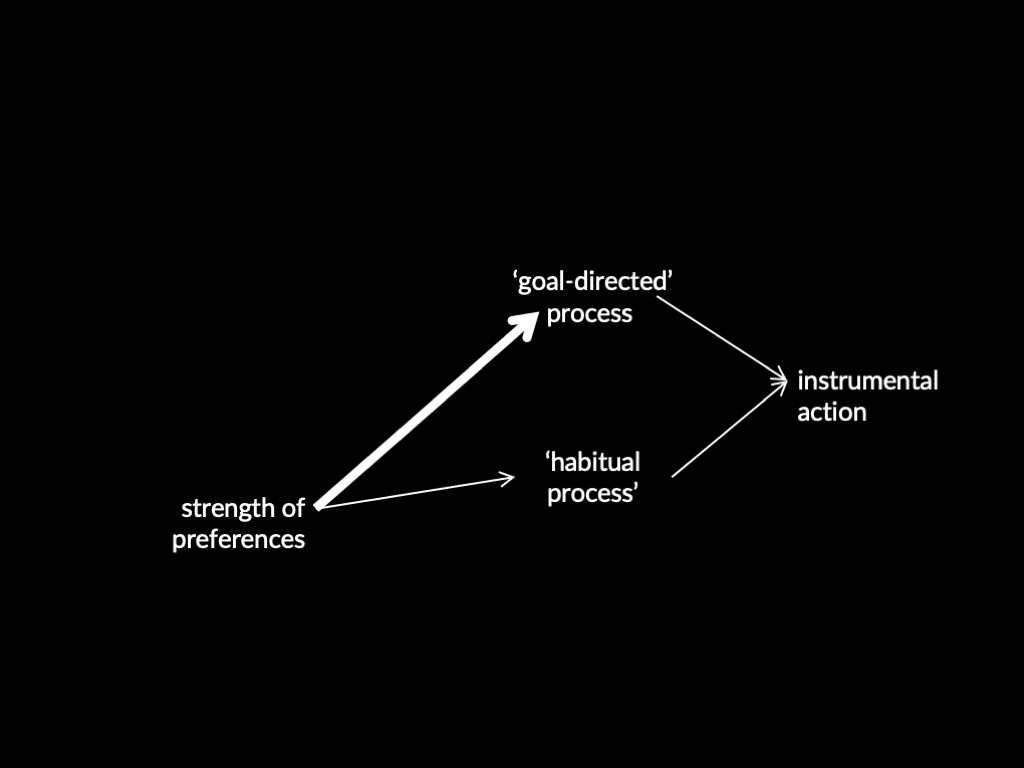

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

‘Who is there that has never wound up his watch on taking off his waistcoat in the daytime, or taken his latchkey out on arriving at the door−step of a friend?

Very absent−minded persons in going to their bedroom to dress for dinner have been known to take off one garment after another and finally to get into bed, merely because that was the habitual issue of the first few movements when performed at a later hour.’

(James, 1901)

Are these habitual?

inconsitent with current preferences -> habitual processes

the same action

can be a consequence of habitual processes

at one time

but not another

Which of these are when are these habitual actions:

doing your teeth;

smoking tobacco;

watching TV;

cycling the same route to work every day?

Is this lever pressing a habitual action?

habitual process

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

‘goal-directed’ process

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

Problem: different hypotheses, same prediction

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

habitual process

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

‘goal-directed’ process

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

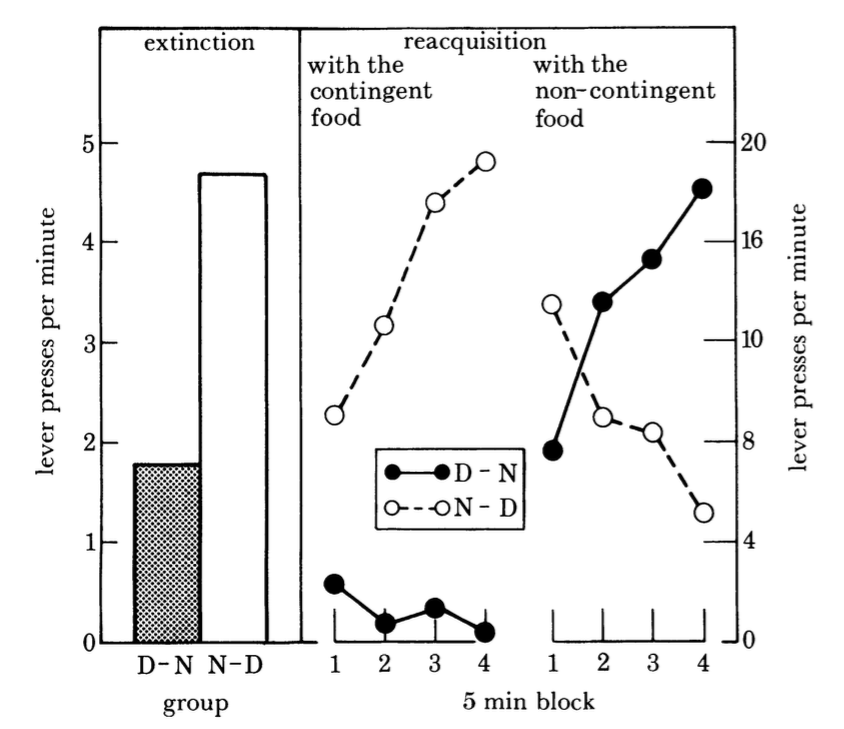

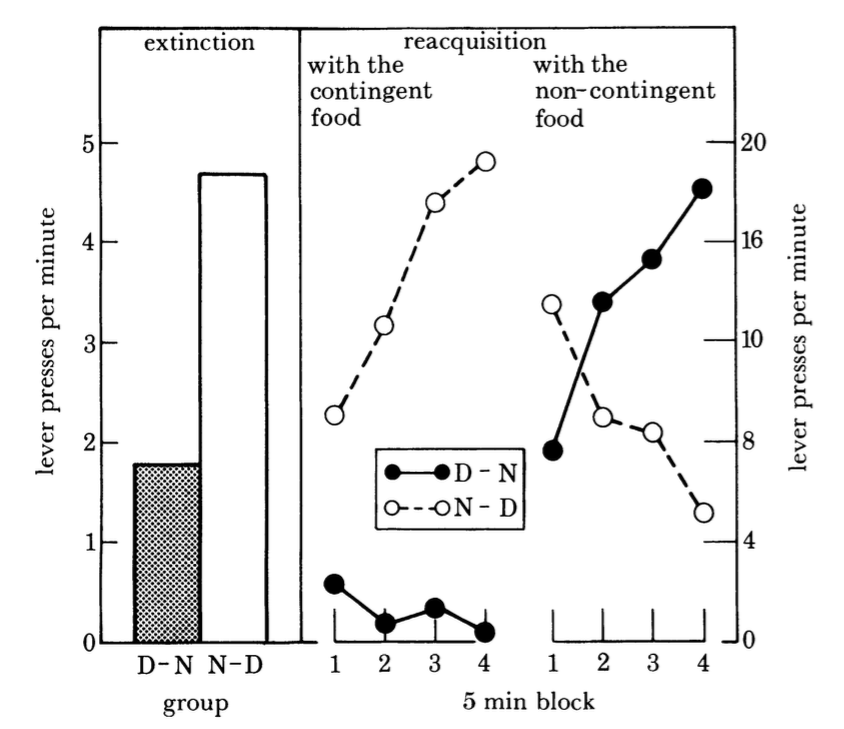

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled by knowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

(Dickinson, 1985, p. 72)

so far ...

1. habitual ≠ habitual

2. What is habitual? processes (not actions!)

3. We can test whether an action is dominated by habitual or goal-directed processes using devaluation in extinction.

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled byknowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

(Dickinson, 1985, p. 72)

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

puzzle

If the action is habitual,

why is it influenced by devaulation at all?

If the action is not habitual but controlled by goal-directed processes, why does it still occur after devaluation?

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled byknowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

Dickinson, 1985 p. 72

‘we did not conclude that all such responding was of this form.

Indeed, we observed some residual responding during the post-re-valuation test that appeared to be impervious to outcome devaluation and therefore autonomous of the current incentive value,

and we speculated that this responding was habitual’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

Dual-Process Theory of Action

some instrumental actions are ‘controlled by two dissociable processes: a goal-directed and an habitual process’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

Is this lever pressing a habitual aciton?

Is this action a consequence of habitual or ‘goal-directed’ processes? Probably both!

Which of these are when are these habitual actions:

doing your teeth;

smoking tobacco;

watching TV;

cycling the same route to work every day?

significance

lokindra427’s question

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

lokindra427:

does it not turn out to be the case that anarchic hand syndrome and habitual processes provide evidence for refuting this claim?

...

lokindra427

In the case of habitual processes [...] can it be said that the agent has knowledge of the reasons for why they act?

What knowledge would they need to have regarding how this habit came about for us to consider the agent as knowing why they are acting in that way?

Does the answer "I did it out of habit" work, or does there need to be something more substantial and/or specific?

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

lokindra427:

In summary, I question the intuitiveness of the claim that we know the reasons for why we act. Maybe we can infer those reasons upon being prompted, but that doesn't seem to be enough.

three types of responses

1. insist that there is knowledge of reasons even when habitual processes dominate actions

2. deny that knowledge of reasons is necessary for intentional action

3. argue that what habitual processes dominate are not actions

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

‘What is essential to behaviour being done for a reason is just that there is a rationalizing relation between the relevant mental state (say, the goal to go running) and the behaviour in question (say, reaching for one’s running shoes), and that the mental state is the (unconscious) cause of the behaviour.’

(Kalis & Ometto, 2021, p. 640)

three types of responses

1. insist that there is knowledge of reasons even when habitual processes dominate actions

2. deny that knowledge of reasons is necessary for intentional action

3. argue that what habitual processes dominate are not actions

The standard model (Davidson’s) ‘specifies the way in which behavior must be caused in order to qualify as a purposeful activity, but not the way it must be caused in order to qualify as an autonomous action.’

(Velleman, 2000, p. 9)

Why make this distinction?

‘When [beliefs and desires] are described as directly causing an intention, and the intention as directly causing movements, not only has the agent been cut out of the story but so has any psychological item that might play his [sic] role’

(Velleman, 2000, p. 125)

(Velleman is attacking Davidson’s model)

three types of responses

1. insist that there is knowledge of reasons even when habitual processes dominate actions

2. deny that knowledge of reasons is necessary for intentional action

3. argue that what habitual processes dominate are not actions

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

lokindra427:

In summary, I question the intuitiveness of the claim that we know the reasons for why we act. Maybe we can infer those reasons upon being prompted, but that doesn't seem to be enough.

What I learned about why you are here