Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Preference vs Aversion: A Dissociation

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

1. two kinds of process -- habitual vs goal-directed ✓

2. two kinds of motivational state -- primary vs preferences

There are at least two kinds of motivational state,

which have distinct roles in explaining behaviour.

anecdote

motivational states

primary motivational states

linked to biological needs, can be unlearned

- hunger, thirst

- satiety

- aversion

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

standard assumption

Primary motivational states are locked to preferences.

For example ..

if you are hungry for a food, you desire it; and

if you are averse to a food, you do not desire it.

1

significance

two motivational systems

2

significance

‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

1. two kinds of process -- habitual vs instrumental ✓

2. two kinds of motivational state -- primary vs preferences

There are at least two kinds of motivational state,

which have distinct roles in explaining behaviour.

step 1

primary motivational states sometimes influence behaviour

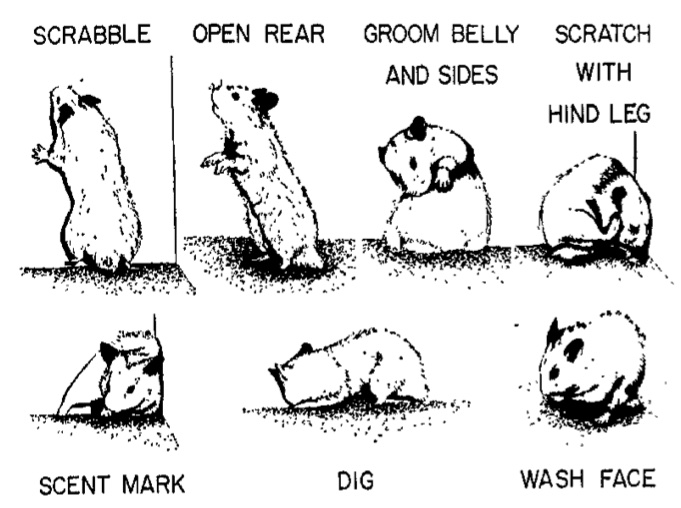

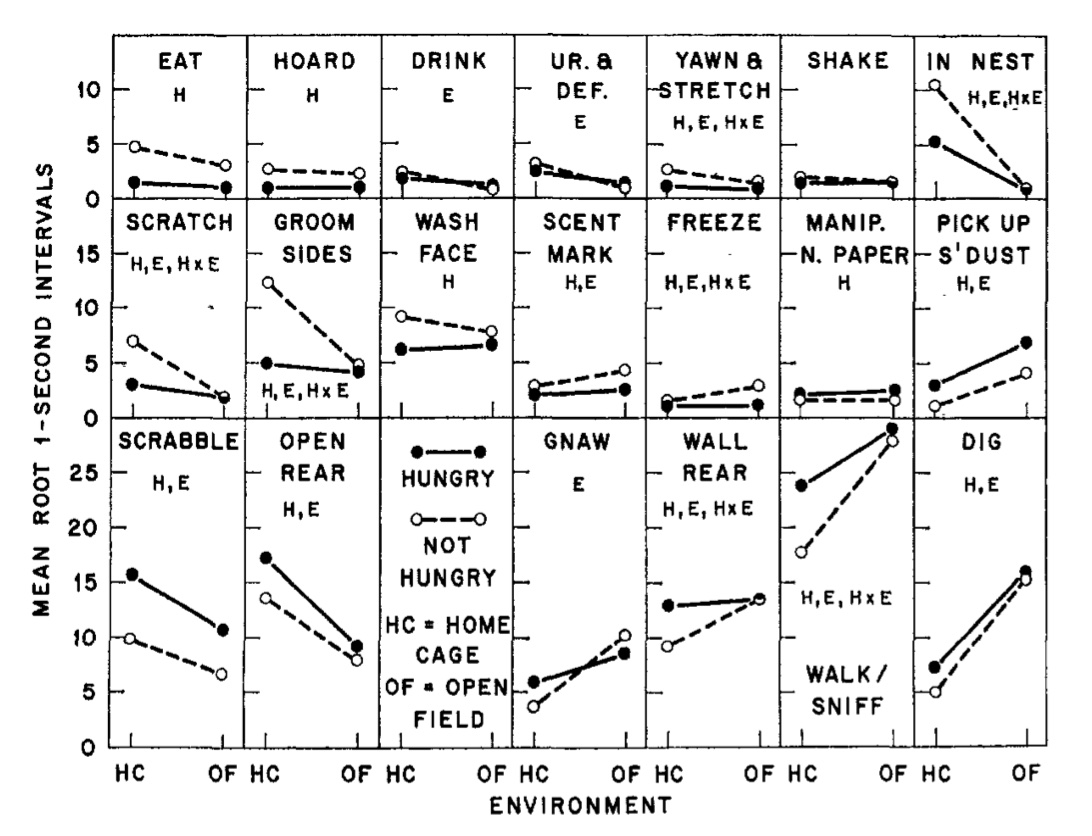

Shettleworth (1975, p. figure 1)

Shettleworth (1975, p. figure 2)

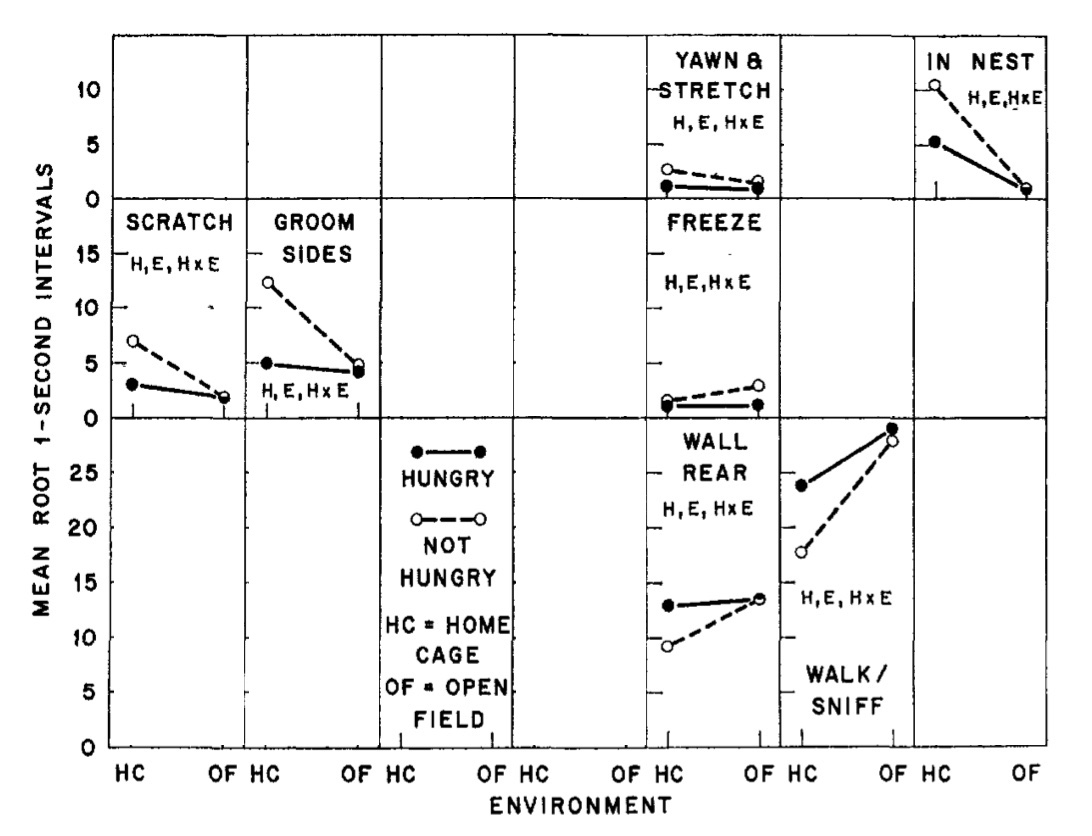

Shettleworth (1975, p. figure 2)

step 2

primary motivational states do not always influence behaviour

I was trained to press the lever for a novel food,

which I retreived from a magazine.

I was trained while satiated

so never ate the food when hungry.

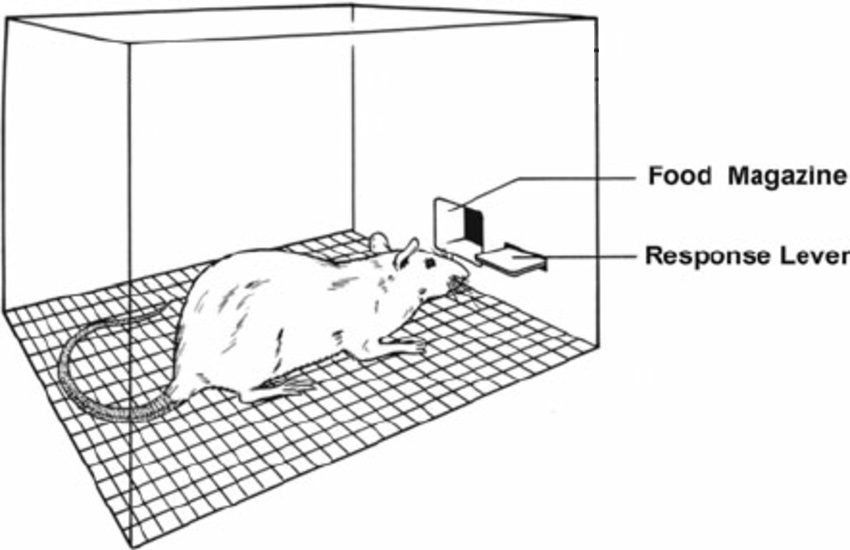

modified from Callahan and Terry (2015) figure 3

After training,

I was tested in extinction.

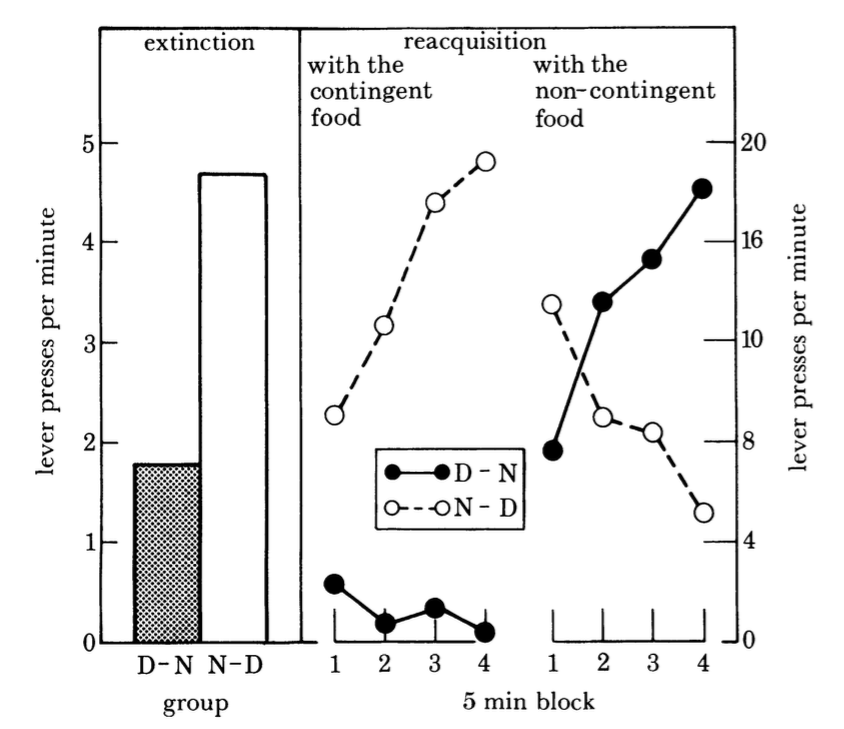

redrawn from Balleine (1992, p. figure 1 (part))

the different actions tell incompatible stories ...

magazine entry

-> when hungry, does desire the novel food (or drink, Exp 1B)

lever pressing

-> when hungry, does NOT desire it

I was trained to press the lever for a novel food,

which I retreived from a magazine.

I never ate the food when hungry.

I never ate the food when satiated.

redrawn from Balleine (1992, p. figure 3)

two actions, incompatible stories ...

magazine entry

-> when satiated, does NOT desire the novel food (or drink, Exp 1B)

lever pressing

-> when satiated, does desire it

same data but just the lever presses

redrawn from Balleine (1992, p. figures 1 and 3)

✓

step 2

primary motivational states do not always influence behaviour

step 3

Why are magazine entries and lever pressing different?

action-guiding processes

outcome driven

driven by expectations concerning how likely the action is to bring about an outcome

stimulus driven

driven by the presence of a stimulus

action—outcome

stimulus—action

e.g. lever pressing -> obtain food

includes goal-directed processes

e.g. enticing smell -> salivation

includes reflexes, habitual processes and more

step 3

Why are magazine entries and lever pressing different?

1. Primary motivational states directly influence

only stimulus-driven processes.

2. Lever-pressing is a consequence of outcome-driven processes.

3. Magazine entry is a consequence of ??? 🐀

conditioning

Pavlovian (classical)

Acquired through exposure to contingencies

Results in stimulus—stimulus links (e.g. bell-food)

The animal responds to the first stimulus as if the second were present

Subject to overshadowing and blocking (u.a.)

Operant

Acquired through being rewarded when acting in the presence of the stimulus.

Results in stimulus—action or action—outcome links.

The animal responds to the stimulus by performing the action.

step 3

1. Primary motivational states directly influence

only stimulus-driven processes.

2. Lever-pressing is a consequence of outcome-driven processes.

3. Magazine entry is a consequence of ??? 🐀stimulus-driven processes.

‘simple anticipatory approach to a food source, such as that involved in magazine entry, is primarily under the control of Pavlovian processes’

Balleine (1992, p. 248)

✓

step 3

Why are magazine entries and lever pressing different?

It is possible to

hunger for it but not want it; and

to want it but not hunger for it.

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

1. two kinds of process -- habitual vs instrumental ✓

2. two kinds of motivational state -- primary vs preferences

There are at least two kinds of motivational state,

which have distinct roles in explaining behaviour.

motivational states

primary motivational states

linked to biological needs, can be unlearned

- hunger

- thirst

- satiety

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

Q1: Can your primary motivational states diverge from your preferences?

For example, can hunger drive you to seek a novel food even tho you have no desire to eat it? And can satiety reign in your search for a food even though you desire to eat it? ✓

For example, can sugar solution rank highly among your preferences even after you have become averse to it?

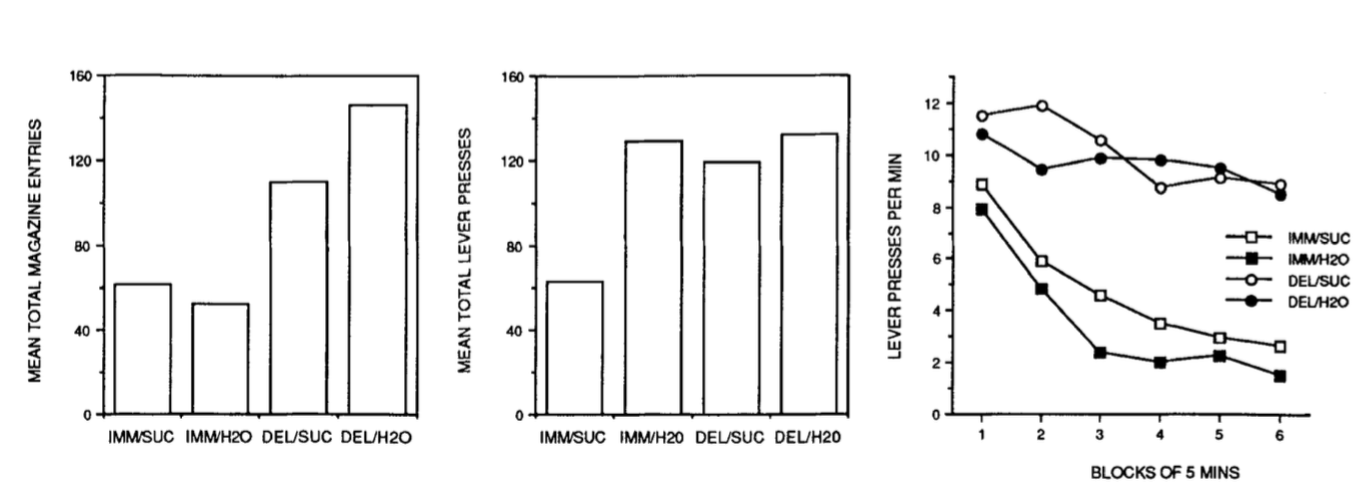

Devaluation - standard procedure:

Training: Rat is put in chamber with Lever; pressing Lever dispenses sucrose (novel food).

Devaluation: Rat is taken into another chamber, poisoned, and then exposed to sucrose.

Extinction Test: Rat returns to chamber with Lever; pressing Lever does nothing.

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3; Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

recap

What causes devaluation?

In the standard procedure, the subjects are poisoned then re-exposed to the food.

Q2: What happens if we poison the subjects but do not re-expose them to the food?

Hypothesis 1: Poisoning does directly influence preferences

Prediction: lever-pressing should reduce (as in the standard procedure)

Hypothesis 2: Poisoning does not directly influence preferences

Prediction: lever-pressing should not reduce (unlike in the standard procedure)

Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

Toxicosis causes aversion to the novel food.

The aversion is manifest in magazine entries, and in reactions when re-encountering the novel food

Aversion to the food is consistent with desire for it.

Method: answer Q1 by answering Q2

Q1: Can your primary motivational states diverge from your preferences?

Q2: What happens if we poison the subjects but do not re-expose them to the food?

Q1: Can your primary motivational states diverge from your preferences?

For example, can hunger drive you to seek a novel food even tho you have no desire to eat it? And can satiety reign in your search for a food even though you desire to eat it? ✓

For example, can sugar solution rank highly among your preferences even after you have become averse to it? ✓

motivational states

primary motivational states

linked to biological needs, can be unlearned

- hunger

- thirst

- satiety

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

1. two kinds of process -- habitual vs instrumental ✓

2. two kinds of motivational state -- primary vs preferences ✓

There are at least two kinds of motivational state,

which have distinct roles in explaining behaviour.

relation to earlier

Suppose the dual-process theory of instrumental action is true.

Can we use decision theory to elucidate the notion of preference (and subjective probability)?

Maybe decision theory characterises only the goal-directed process?

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished] p(class=theCls)Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

Concerning the habitual process, what makes outcomes rewarding?

possibility 1:

the very system of preference that is involved in the goal-directed process

possibility 2:

not the system of preference that is involved in the goal-directed process 🐀

interim conclusion

Philosophical and formal theories of action and joint action

assume a single system in which

belief, desire, intention and the rest

are normatively

and inferentially

integrated.

One instrumental action can involve multiple, dissociable

motivational states

and multiple, dissociable

goal-selection processes.

This gives rise to interface problems.

An interface problem ...

‘we should search in vain among the literature for a consensus about the psychological processes by which primary motivational states, such as hunger and thirst, regulate simple goal-directed [i.e. instrumental] acts’

Dickinson & Balleine , 1994 p. 1

two motivational systems

An Interface Problem:

How are non-accidental matches possible?

Primary motivational states guide some actions.

Preferences guide some actions.

Pursuing a single goal can involve both kinds of state.

Primary motivational states can differ from preferences.

Two motivational states match in a particular context just if, in that context, the actions one would cause and the actions the other would cause are not too different.